Space Needle

As a person who would like to have the Space Needle engraved on her tombstone when the time comes, it seems fitting to begin a blog called Loving Seattle with the Needle.

I hope the visions of a better future fill you as you read this story about its grace born out of the most troubling days of the Cold War.

Seattle pre-1962

Before the Century 21 World’s Fair with the Space Needle as its symbol, Seattle was a town of half a million people, Boeing and Safeco. It was nearly non-existent in the context outside of its own. So much so, that foreigners had to have it pointed out on the map, and East Coasters sometimes called it Seetl. That is, when they had a reason to call it anything at all.

The year 1962 shifted the paradigm. But first, about the times.

The Times

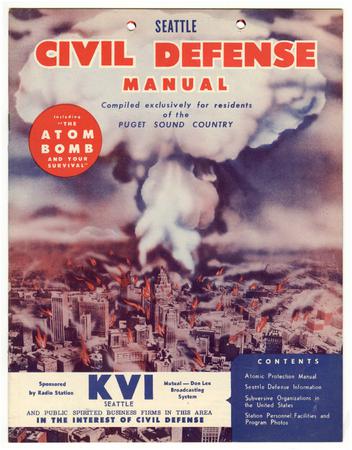

The year-and-a-half between the day of ground-breaking for the Space Needle and the last week of the World’s Fair was sandwiched between the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis. During that period, from the beginning of 1961 to the end of 1962, the Berlin Wall, the very embodiment of the Iron Curtain, was being raised and crowned with barbed wire physically dividing the worlds of Europe. And here, in Washington State, the Hanford Nuclear Site, the birthplace of the Fat Man of Nagasaki’s plutonium, was at the height of its production.

Fallout shelters were everywhere, as well as the evacuation route street signs. Kids were learning to duck and cover at schools, and atom bombs were being tested in pristine nature with open public viewings.

Everyone was being primed for an imminent nuclear attack as the countries looked at one another through gunpoint.

The prospects of the future were bleak indeed. Not entirely unlike today.

And yet, in all that doom and gloom, there sprouted a tower. It stretched upwards, attempting to grasp the stars and inviting competition in beauty and technological achievements. Back in 1962, one might even imagine it leaping into the future.

It brought so much joy and pride.

The four concepts that fused the Space Needle into what it became were technological prowess, tragedy and a recovery mission, grace, and collective dedication.

As these concepts shaped the tower, an undergirding to ensure the Needle’s long life was financial self-sufficiency. In a town where some attempt to indiscriminately demolish its architectural and cultural heritage in the name of a so-called “renewal,” financial stability proved to be prophetic.

Technology, Tragedy and a Recovery Mission

When John Graham Jr. was chosen as the Space Needle’s chief architect in 1960, he had a very specific idea for it. It had to have a rotating disk-shaped top house with a restaurant inside. The restaurant was to secure a constant flow of money, and the “disky” shape was to imitate a flying saucer of our imaginations.1

The phrase “flying saucer” is as much Seattle’s as, say, the view of the sugar-covered Mount Rainier. It was coined in a 1947 recovery mission for the bodies of 32 Marines whose transport plane crashed on Mount Rainier the year before. When the aircraft debris was spotted in the summer of 1947, some private pilots joined the search party. As one of those pilots flew over Mount Rainier, he described seeing nine flashing objects coming toward him. The media immediately dubbed it “flying saucers.”

Graham’s top house, therefore, had to be “disky.” I like to see it as a memory of the 32 Marines still trapped in a Mount Rainier glacier2 but also as a play on our collective imagination that came from the phrase.

But then, Graham also wanted this flying saucer to rotate. Back in 1960, there was only one rotating restaurant in the United States, and it was Graham’s own design in Honolulu. A brilliant innovator and a visionary businessman, Graham patented a gearing system that could revolve a restaurant with 250 people inside, guess this—on one horse-powered electric motor! That is the same power that runs a washing machine.

But in the summer of 1960, Graham was still searching for the right design for the tower topped with a rotating flying saucer restaurant.

Grace

As thousands of design drafts were being submitted, none satisfied Graham. He decided to commission a University of Washington professor Victor Steinbrueck, the one who soon after “put the curve in the Needle.”3

In his diary, Victor Steinbrueck wrote that the inspiration for his tower was his friend David Lemon’s sculpture, The Feminine One—an abstract dancer in motion with tripod legs, slender waist and arms that reach up to the skies. Lemon’s inspiration for The Feminine One, on the other hand, is thought to be Syvilla Fort, a Seattleite and the first Black dancer to graduate from the Cornish School (Cornish College of the Arts today).

We can all see this statue as a large bronze reproduction standing in front of the Space Needle.

Why would Lemon’s sculpture remain on Steinbrueck’s desk for years, looking at him as he worked? It is said that Steinbrueck and Fort had a romantic relationship decades before their mutual friend Lemon sculpted The Feminine One.4 If that is the case, then it is no wonder that Lemon gifted his statue to Steinbrueck, and that it stood on the architect’s desk waiting to inspire the Needle.

It is worth noting that segregation prevented Syvilla Fort from finding dancing success in Seattle, and so she went to New York City. By the time Steinbrueck designed the Space Needle’s stem, however, Fort had made it big as a famed choreographer of a transformative drummed dance style, and taught the likes of James Dean and Marlon Brando in Manhattan. Sadly, she is still far more known in NYC than she is in her hometown.

I like to imagine her as the spine of the Needle.

Envisioning

Looking at the Space Needle, we could see three dancers, standing back-to-back in a circle, legs and arms apart, their bodies stretched, their arms reaching towards the skies and balancing a flying saucer on them.5 We might see this steel-made paradigm of grace and know that its beauty is grounded in so much concrete, it could withstand a 9.0 earthquake.

We might also imagine the organizers back in 1960 flying a small airplane to determine the height for a most pleasing view from the observation deck and the restaurant. They did not want it too high to detach us from “life on earth” or too low to take away the sense of levitating above the world.6 The reason we see spectacular views of the city flanked by unrivaled nature—Mount Rainier, the Cascades and the Olympics—is precision.

Dedication

We can also think back as it was being built in 1961 and see a vast collective effort that made it possible.

The rail tracks that brought the steel beams came from the U. S. Steel’s Chicago mill. American-made of course. We could imagine the beams being welded, heated and shaped to give a waistline at the Pacific Car and Foundry in Seattle.

Then we could imagine the ironworkers.7 The cables hoisting them up in a bucket with little protection from a fall. Often beginning their workdays at 3 am and finishing at 4:30 pm for just under $4 per hour. Then we could hear some of them admitting their fear of heights, but determined to work 400 and 500 ft above ground, often with no harness, despite 60 mph winds and snowstorms, and continually threatened by the swaying steel cables. And yet, in all our dire imagination, we are assured that the worst injury in building the Space Needle was a broken arm.

As we read about the circumstances under which the ironworkers labored to make the Needle for us to love, it must make us happy to know that the first dinner on top of the Space Needle was served to them, the workers who built it. They took so much pride in their structure, that when the American flag they posted on top was taken down and replaced with a Christmas tree, they were outraged. The Needle belonged to them, just as much as it belonged to the visionaries, the artists, the investors, the city officials, and of course, to all of us, past, present and future Seattleites.

But that is not all.

More Ingenuity

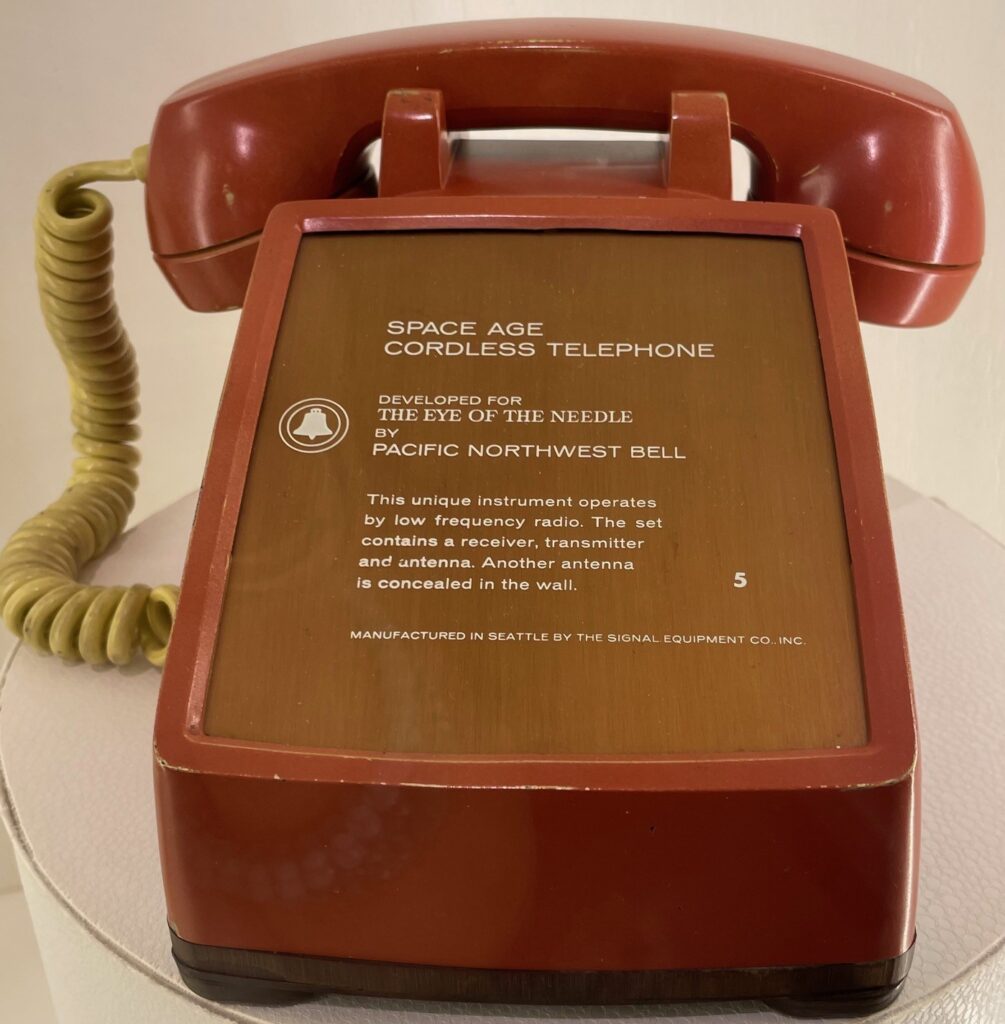

When the Space Needle opened, it shocked its visitors with yet another technological feat. As if not enough that the Space Needle’s rotating restaurant ran on a one-horse powered motor, and that a capsule elevator flew up 600 feet in only 43 seconds in the thrill of a rocket launch, the restaurant tables had wireless telephones!

Since the restaurant continually turned, telephones could not be plugged in. And so, the Pacific Northwest Bell engineers created wireless telephones for the Space Needle, their “Space Age Cordless Telephones.” These gadgets that grew into what we all know intimately today were manufactured in Seattle for the Space Needle. They had a radio transmitter hidden in the wall enabling the diners to lift the receiver and get connected to the operator right from their tables.8 Pretty unheard of in 1962.

Why It Matters

The Needle in my mind proves that grace could sprout out of the coldest of the Cold War with segregation still very much alive. It represents the unifying beauty of Syvilla Fort’s movement, the recovery mission for the 32 Marines’ bodies, unheard-of technological prowess, the collective labor and love that engaged so many. And all that plus a sustainable financial future to ensure its preservation.

As I see it, one person, one effort, one vision, leads to another and another and another in a cascading effect, uniting people to create beauty and invite others to compete in advancements that are good for everybody.

Maybe you are the one to jolt a vision of a better future for all of us?

With love,

Mira

- The image under the subtitle Seattle pre-1962: Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives, identifier 167457, link

- The image under the subtitle The Times: Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives, identifier 9900_01_001_006_002, link

- The image under the subtitle More Ingenuity: Courtesy of the Connections Museum Seattle

- The image under the subtitle Why It Matters: Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives, identifier 196743, link

- The rest of the images are my own.